Women occupy roughly one in three junior academic positions in economics and just one single in four senior positions, in accordance with an analysis of gender equality at the field’s top research institutions.

Most previous surveys examining equality in economics have centered on individual countries. Emmanuelle Auriol, an economist at the Toulouse School of Economics in France, and her colleagues compared gender representation around a lot of the entire world, although their data set includes few institutions in Africa or Southeast Asia. The findings are published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences1 this month.

To compile the information set, Auriol’s team created an algorithm that scraped details including gender and job title for 96,044 employees from those sites of 1,383 economics research institutions. The team then sorted these positions right into a hierarchy to take into account differences constantly in place titles between regions: full and associate professors were classed as senior-level positions, assistant professors and lecturers as entry-level positions and Ph.D. students as research associates.

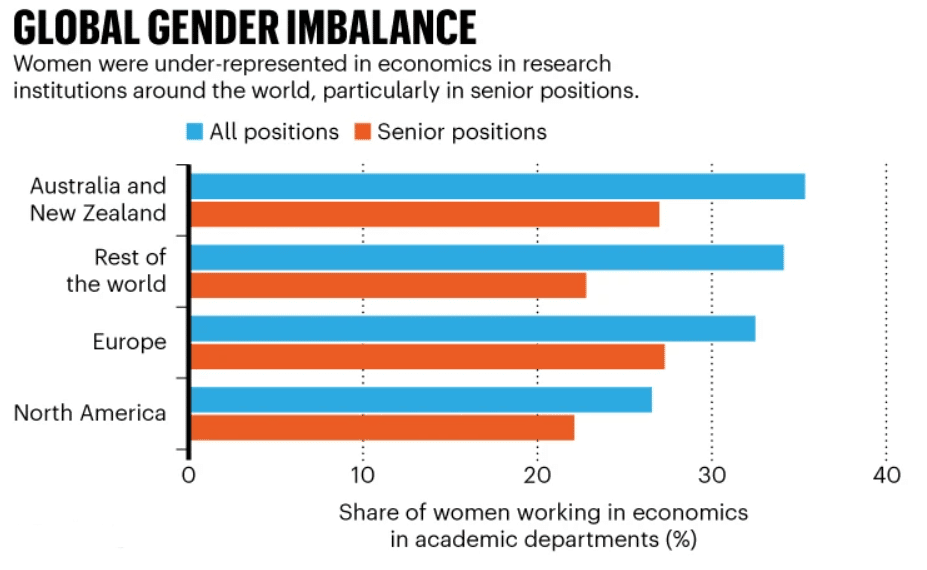

In this data set, women occupied only 32% of most economics positions, using their representation declining from research associates and entry-level positions (40%) to senior levels (27%).

“It is rather striking if you ask me why these patterns that people see of a leaky pipeline are prevalent across the planet,” says Anusha Chari, an economist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Revealing transnational disparities

According to their main analysis, the researchers limited the info to the most effective 300 institutions by research output, nearly all in Europe and North America. For these institutions, they discovered that Australia and New Zealand had the greatest percentage of ladies in the field, at 35%. Europe had 32% and North America 26%; the remaining part of the world had 34% (see ‘Global gender imbalance’).

US research institutions had lower proportions of women at every rank than European institutions, and the difference was most marked at the senior level. The team compared regions in Europe and the United States and found that women occupied more than 50% of senior positions at Romanian institutions, but only around 20% in Greece, Germany and the Netherlands. In the United States, the lowest proportions of economists who are women were in the West and the highest in the South.

Their analysis also showed that institutions ranked highly in terms of research output have fewer women in entry-level positions than do lower-ranking institutions, suggesting that women are not being hired at the same rate as men for those roles. This was particularly striking in the United States. “It’s not proof, but we believe that — in light of all the literature that comes before us — surely there’s some discrimination going on,” Auriol says.

Minding the gap

Previous research has found that the work culture in economics can be aggressive and hostile towards women, exacerbated by factors such as discrimination, inappropriate behaviour, elevated criticism, skewed tactics for hiring and promotion, and stereotyping — all of which could contribute to the gender gap 2–4. Still, “it would be naive to think any one of them is the smoking gun”, says Vida Maralani, who studies quantitative sociology and social inequities at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York.

Auriol and her team highlight the consequences of the gender imbalance in economics, including fewer suitable employees for institutions to hire, and a lack of role models for women entering the field. Furthermore, women are more likely than men to research topics such as health and education, so future studies could be “tilted towards the topics that are favoured by men, which are not necessarily the ones that matter most for society”, Auriol says.

Solving this systemic problem will require shifts in culture, practices and policy, says Chari. She says economists must first accept and recognize the bias in the field. Increasing mentorship and networks for women will also give them the tools to better navigate the profession. “I think we need to study the problem and to document it so that it is very hard for people to deny it — to pretend it doesn’t exist,” Auriol says.